In October of 2015 Joshua J. Lynch, DO, a clinical assistant professor of emergency medicine in the Jacobs School and a physician with UBMD Emergency Medicine, read a paper that introduced him to the idea of Emergency Department based medication assisted therapy (MAT).1 The paper, published at Yale concluded that patients who were given buprenorphine in the ED and provided with a clinic appointment were the most likely to be in treatment a month later and the most likely to have reduced their opioid use. As an emergency room physician in a region of New York, where that year 800 people would die from opioid overdoses alone,2 Lynch jumped at the opportunity to do more for these patients than simply hand them brochures of treatment options (the standard of care at the time).

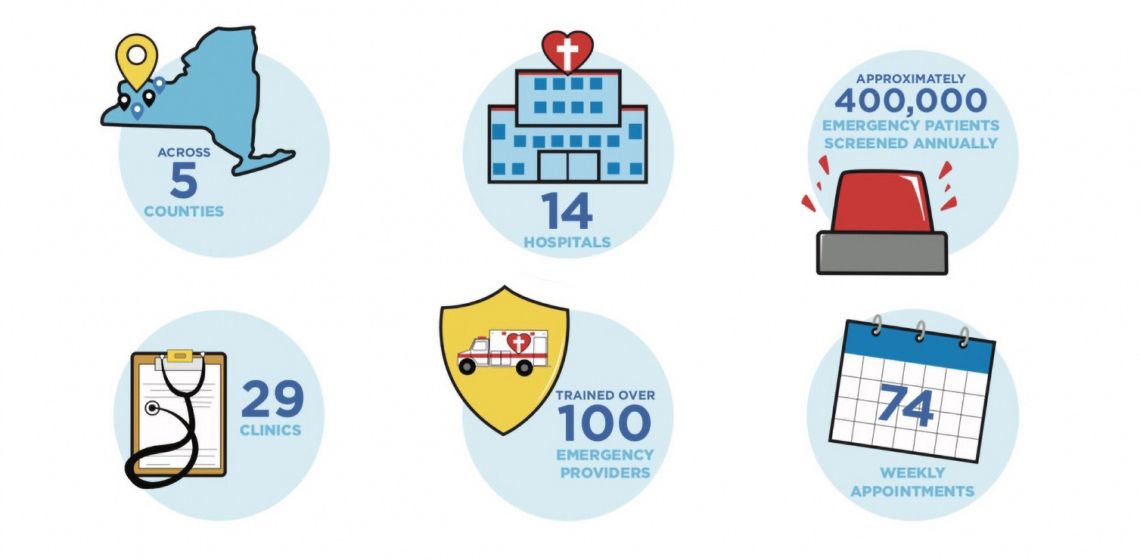

Lynch immediately underwent MAT training, encouraging his colleagues to do the same and then worked with his colleagues to develop a standardized patient management protocol. They began to treat these patients with MAT and after each treatment. A series of phone calls were made to local clinic directors, asking them to squeeze in patients for follow-up appointments. This process was time consuming and there was no way to guarantee that all the patients could get spots in the clinic. In response, Lynch founded The Buffalo Medication Assisted Treatment & Emergency Referrals program (Buffalo MATTERS). Buffalo Matters was designed as a network of local hospitals and community clinics whose collaboration was designed to help bridge the gap between Emergency Department assisted MAT and follow-up treatment in the community.

One aspect of the Buffalo matters program that differentiates it from other programs that provide medication assisted therapy and subsequent referral to care is its sheer convenience. The program boasts an average 48-hour turn-round-time and a variety of referral facilities that allow patients to peruse treatment at a location that is easily accessible. The number of community clinics that participate in Buffalo MATTERS allows patients to have choices; a rarity in the world of free and reduced cost health services.2 “The patient in withdrawal who drives to the emergency room because they know they need help is typically looking for a way to get better,” explains Lynch. “When you hand them a list of 64 clinic appointments with 27 different locations they can choose from, they get interested.”2

Though no official numbers have been released, Erie County health commissioner Dr. Gale Burnstien has reported a decline in overdose death rates since the implementation of the program.3 Now operating in 13 hospitals in western New York, the program is hoping to expand throughout the regions eight counties and eventually beyond. Armed with $200,000 from the Blue fund of BlueCross Blue Shield, immediate plans include expansion into six new hospitals as well as continued recruitment of community clinics.2

References

- D’Onofrio, G., O’Connor, P. G., Pantalon, M. V., Chawarski, M. C., Busch, S. H., Owens, P. H., … Fiellin, D. A. (2015). Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 313(16), 1636–1644. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.3474

- Goldbaum, E. (2018, November 12). In Buffalo ERs better way to treat opioid use disorder - UB Now: News and views for UB faculty and staff - University at Buffalo. Retrieved from http://www.buffalo.edu/ubnow/campus.host.html/content/shared/university/news/ub-reporter-articles/stories/2018/11/opioid-treatment-ER.detail.html

- Drury, T. (2018, November 21). Local efforts making a dent in opioid crisis, experts say - Buffalo MATTERS. Retrieved from https://buffalomatters.org/2018/10/26/local-efforts-making-a-dent-in-opioid-crisis/

Rebecca Siegel, is a research fellow in the GWU Department of Emergency Medicine and a medical student at Ben Gurion University in Israel.