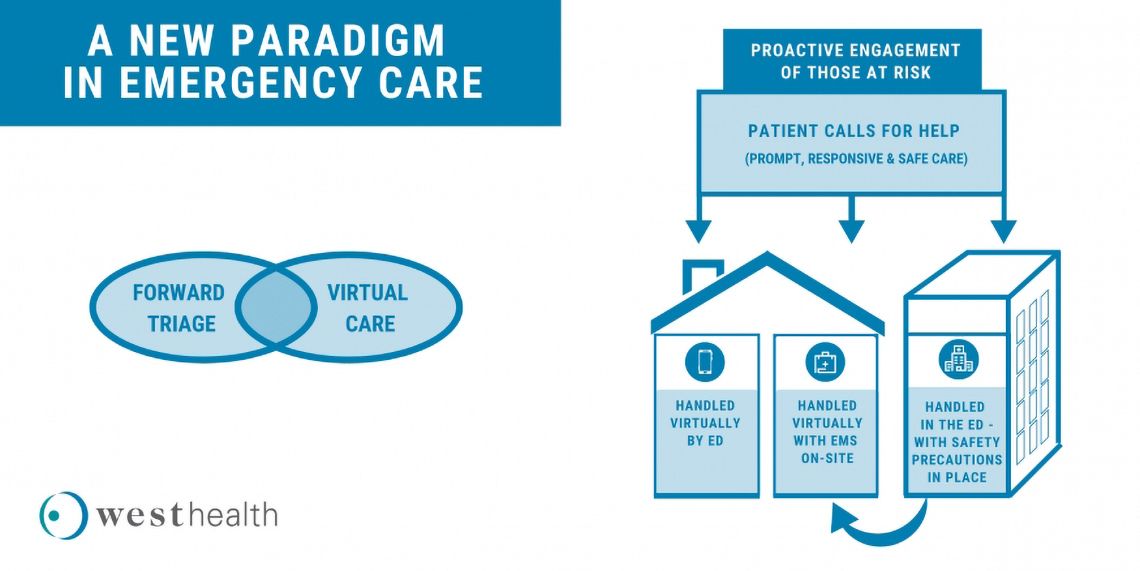

Today, emergency room physicians see too many patients who have delayed treatment for heart attacks, strokes, and other serious conditions because of COVID-19 fears. In some cases, the results are needlessly catastrophic. Decisions to activate emergency care for life-threatening episodes appear to be dominated by perceptions that our nation’s emergency care infrastructure is either overwhelmed or unable to safely manage a call for help. As the number of COVID-19 cases in the US has crossed the threshold of 2 million people, four in five adults say they are concerned about contracting COVID-19 from another patient or visitor if they need to go to the emergency department (ED), while nearly a third report actively delaying or avoiding medical care. These concerns appear to manifest as reduced ED visits, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reporting a 42% drop in ED visits and so-called excess deaths, including deaths that may be associated with avoided or delayed care. Older adults are admittedly in a particularly precarious situation. They are among the highest risk for complications and mortality from COVID-19, yet they can least afford to postpone or avoid receiving acute health care for other serious illnesses, injuries or exacerbations of chronic conditions. The COVID-19 crisis has greatly increased the imperative to develop a new paradigm of emergency care for older adults. We propose that policymakers, administrators and the broader clinician community collaborate with emergency medicine professionals to support a three–pronged approach:

- Proactive outreach to older and high-risk individuals, making sure they and their caregivers know why, how and when to activate needed care

- Redesign of the emergency care response system to provide acute medical needs in the home if possible

- Ensure ED environments and processes are safe and senior-friendly

1) Proactive Outreach for High-risk and Chronically Ill Patients

A first step to help older adults with chronic illness exacerbations safely receive needed care is to reassure them of the importance of receiving timely care. Among older populations, decompensated heart failure, exacerbations of chronic lung disease, and complications of periodic infections are ubiquitous. Emergency physicians need managed care administrators and the primary care community to reach out to their highest risk patients, spelling out the relative risks of delaying treatment for urgent and emergent conditions. Outreach can consist of mailers, emails, text messages, and even in-person phone calls. There are many examples of healthcare systems—especially those who are most financially at-risk—successfully mobilizing communication campaigns to reach their vulnerable senior populations. The West Health Institute (WHI) and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) have been working with numerous risk-bearing organizations in a home-based acute care learning and action network (HomeLAN), developing proactive outreach as described above. Using Chronic Care Management (CCM) services, for example, successful organizations have provided their highest risk patients clear color-coded health indicators of when and why to call for help, making sure they are placed near a patient’s telephone or on the refrigerator.

Proactive outreach can help EDs by spelling out what types of responses patients might expect upon activating care. For example, rather being told to hang up and dial 911, primary care providers can reach out to patients in their panel with chronic disease to ensure they do not need immediate care, and if emergency care is needed, coordinate optimal care delivery with ED providers. But more importantly, provider outreach will benefit most when they can elaborate a specific range of options that extend beyond the four walls of the ED. As described below, a well-communicated commitment to providing care where most safe and appropriate, including receiving that care in the comfort and safety of their homes and communities. Building from this initial commitment, providers can overcome the initial reticence to call, both for suspected COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 related issues. If a transfer to the ED is warranted, the initial engagement provides a context for a meaningful discussion about safety measures in place, and the relative risks of delayed care versus exposure to COVID-19. Beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, policies supportive of proactive outreach can lower hospital-related spending and increase days-at-home—both critical metrics of cost-effective, senior-focused healthcare.

2) Care at home as much as possible

a) Telehealth for seniors:

The COVID-19 pandemic has instigated revolutionary advances in telehealth and telephonic care delivery, many of which are included in the so-called “hospital without walls” policies set in motion by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Policymakers and value-based care administrators need to make sure the gains in telehealth and telephonic care persist beyond the current pandemic, especially for older adults. Telehealth and telephonic care allow seniors to be treated safely at home, when possible. When not possible, the initial engagement afforded by telehealth and telephonic care allows providers to indicate next steps, such as an in-person office visit, urgent care, or immediate ED-based care. Organizations in the WHI/IHI HomeLAN augmented proactive outreaching as described above to support virtual management of early onset events, for example adding or modifying prescriptions as well as broader office level services and triage to the most appropriate site of care.

b) Emergency Medical Services (EMS) bringing the care to the patient rather than the patient to the care site:

For unplanned acute care needs, especially exacerbations of chronic disease, EMS services such as ED evaluation and management as well as observation services can be engaged and reimbursed via telehealth delivery. Emergency physicians require someone on-scene, administering oxygen, for example, or monitoring vital signs such as heart rates or blood oxygenation levels. These functions are all part of the so-called prehospital care that paramedics routinely provide. In the HomeLAN, telehealth-enabled EMS responses were ramped up to nearly 60 cases per week, ultimately keeping hundreds of patients out of the ED in April 2020 alone, especially in the COVID-19 hotspots such as New York City. However, achieving this ramp up in EMS services required providers to separately contract with ambulance companies. While some of these contract expenses can be offset by provider-side billing, not all expenses are covered. Moreover, even in the COVID-19 emergency, CMS is only able to cover these paramedic services when they culminate in a transport, albeit with a temporarily expanded list of allowable destinations. Unfortunately, many of these alternate sites such as skilled nursing facilities may provoke the same fear-based avoidance of emergency care as a whole. We recommend that CMS expand pre-hospital services to include treatment in place (TIP), meaning pre-hospital care—under the direct supervision of an emergency doctor— can be reimbursed when delivered in the home. Patients need to know that if they call 911, they will only be transported to the ED if the specific care they need can only be delivered in an ED. A new CMS demonstration program known as Emergency Triage, Treat and Transport (ET3) includes options for TIP, but program rollout was delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic. We recommend that CMS consider either adding treatment in home to the current emergency waivers for ambulance services, or else consider accelerating the rollout of ET3, especially to current TIP awardees. Importantly, our recommendation for TIP should be viewed within the context of ED-managed oversight and forward triage of overall ED care, as opposed to any type of substitution or alternative to ED supervised care. Because EMS volumes are down during COVID-19 pandemic, reimbursement for home-based pre-hospital care services could alleviate business pressures as well as reduce potentially catastrophic consequences of deferred care.

3) Best practices for a safe, senior-friendly emergency room

Despite the beneficial engagement afforded by telehealth and home-based care options, the need to escalate care to the ED will arise. Fortunately, many best practices in providing safe emergency care during this pandemic have been created and now need to become standard practice across our country. These best practices in safe care include:

a) Triage before the Emergency Department (Forward Triage):

All EDs need to be safe places where seniors do not have to worry about contracting COVID-19. To do this, patients who exhibit possible symptoms of or exposure to the virus need to be treated in a separate space from patients who do not have COVID-19. EDs also need to be connected to outpatient clinics so that if the initial assessment determines the patient does not need to be treated in the ED, the patient can be referred for same-day clinic visit. Properly done, tent triage outside the ED results in multiple possible pathways including : 1) Coming into an ED area where suspected COVID-19 cases are assessed, 2) coming into an ED area where there is unlikely to be COVID-19 patients, 3) using telehealth to assess and treat in the patient’s car and not having to come into the ED at all, or 4) rapid, often same-day referral to urgent care or primary care clinic.

b) Safe Emergency Department Space

Waiting room safety:

If tele-health and foreward triage are utilized correctly, waiting room times should be minimized. However, having to wait is always a possibility. Ensuring a safe, clean space with adequate distance between people waiting to be evaluated is necessary to avoid infection spread while waiting. Even better, innovative scheduling software exists to schedule urgent but not truly emergent visits.

Eradication of all hallway beds:

Many EDs utilize beds in the hallway to manage overflow, often because patients wait in the ED for long periods of time before having a bed available to move to an inpatient room. This is unacceptable. Staying in the hallway is dangerous for older adults as it may cause confusion and delirium, falls, bed sores, complete lack of privacy, and especially now, could expose the patients to infectious diseases including COVID-19. Hallway beds need to become a thing of the past.

Personal Protective Equipment:

All ED staff, patients, and visitors need adequate, readily available personal protective equipment at all times. Period.

c) Caregivers are critical:

Older adults, and their caregivers, are scared to come to the ED because they know the patient’s loved ones will likely not be allowed to come in with them. While this is understandable from an infection control standpoint, older patients, especially those with dementia, need their advocates and caregivers. If those caregivers feel comfortable coming into the ED, we should welcome them, with appropriate protective equipment available for them. Caregivers are a critical part of the care team and without them, older adults are at increased risk of delirium, agitation, and injury. It is becoming increasingly clear that patients are avoiding critically important health care because no caregivers or visitors are allowed to accompany them. Processes for triage can be implemented to extend isolation to patient dyads, for example, alleviating much of the concern.

d) Rapid COVID testing availability

COVID - 19 testing with rapid turnaround is now available. Knowing whether a patient likely has COVID - 19 minimizes any other care delays such as radiology imaging or hospital admission, minimizes the chances another patient is exposed to a COVID - 19 positive patient, facilitates safe transfers to skilled nursing facilities and other congregate living centers, and is critical to providing safe ED care. Furthermore, rapid testing availability for healthcare staff with a regular testing schedule is equally critical to ensure a safe ED environment for all patients and staff.

e) Safe transitions to home from the ED:

If ED providers admit patients to the hospital for lack of social or well-integrated out-patient medical resources, patients will be reluctant to come to the ED as they do not wish to be contained in a hospital that has other patients with COVID-19 and may not allow them to have their friends or family visit. There are well defined best practices in care transitions for older adults from the ED to outpatient settings including working with case management, social work, home health agencies, physical therapy, and pharmacy to create a safe transition home from the ED to avoid medically unhelpful hospital admissions. The American College of Emergency Physicians Geriatric ED Accreditation Program, with over 150 accredited EDs, outlines many of these best practices.

The COVID-19 crisis has generated a heightened sense of emergency departments as portals to the entire healthcare system: if patients don’t get ED care, they forgo critical, life-saving care available not just in the ED, but well beyond. We have proposed a three–pronged approach, built off learnings from the HomeLAN as well as best practices of accredited Geriatric Emergency Departments, to help ensure safe emergency care for older adults and all other patients frightened to come to the ED today.

We ask that policymakers, administrators, and the broader clinician community join the growing group of stakeholders who are adopting and advancing these approaches, ensuring that America's seniors can once again safely seek emergency care.

Kevin Biese, MD, MAT

Dr. Biese serves as an Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine (EM) and Internal Medicine, Vice-Chair of Academic Affairs, and Co-Director of the Division of Geriatrics Emergency Medicine at the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill School of Medicine as well as a consultant with West Health. With the support of the John A. Hartford and West Health Foundations, and alongside Dr. Ula Hwang, he serves as Co-PI of the national Geriatric Emergency Department Collaborative. He is grateful to chair the first Board of Governors for the ACEP Geriatric Emergency Department Accreditation Program.

Jon Zifferblatt, MD, MPH, MBA

In his role as Executive Vice President, Strategy and Successful Aging, Dr. Jon Zifferblatt advances West Health’s mission to lower healthcare costs to enable seniors to successfully age in place with access to high-quality, affordable health and support services that preserve and protect their dignity, quality of life and independence.

At West Health, Dr. Zifferblatt creates and implements our strategic successful aging initiatives, as well as co-managing our platform focused on lowering the cost of healthcare. Under his leadership, the organization is focused on driving integration across its successful aging clinical research portfolios, models of excellence and cost of healthcare strategic initiatives. Ensuring that the work done by West Health has a maximal impact – at scale – for older adults is a key area of his focus.

Prior to joining West Health, Dr. Zifferblatt has had previous roles in the population health, evidence generation, and healthcare business sectors, and has served in a variety of executive, research, and clinical capacities in the U.S., China, and Japan.

A California native, he completed undergraduate work at Stanford University, received his medical degree from UC San Diego, and a combined MBA/MPH from UC Berkeley.

Amy R. Stuck, PhD, RN

Amy Stuck is Senior Director, Value-based Acute Care and a health services researcher at the West Health Institute, a non-profit medical research organization focused on senior-specific healthcare delivery innovations to lower the cost of healthcare and enable successful aging in place.

Amy earned her Bachelor of Science in Nursing from the University of Portland, her master’s degree in Nursing Education from California State University, Dominguez Hills, with an emphasis on hospital acquired infections, and a PhD in Nursing from the University of San Diego with a focus on ICU Delirium. She completed post-doctoral studies in the Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of California, San Diego studying healthcare utilization prior to deaths by suicide and unintentional lethal opioid overdoses.

Amy’s current fields of study include senior-focused emergency care, home and community-based alternatives to hospitalization, value-based care in Medicare and accountable care organizations.

Amy has over 30 years’ experience in Acute and Critical Care nursing, quality improvement, hospital leadership and nursing education.

Christopher Crowley, PhD

Dr. Christopher Crowley is a systems engineer and quantitative analyst with a career dedicated to public health, safety and wellbeing. His research interests include population health, health disparities, community-based care and surveillance as well as the development and navigation of successful aging throughout the continuum of care. Dr. Crowley received a PhD in Electrical Engineering from McGill University and Certificate in Quantitative Finance. He holds over 20 patents and currently serves as a Program Manager at the West Health Institute.